We are proud to highlight the work that our stakeholders undertake to make progress towards achieving Vermont’s clean transportation energy future by reducing petroleum usage in equitable and just ways.

Every month, we highlight one of our stakeholder’s efforts. Let us know if you’d like to be included in an upcoming Stakeholder Spotlight!

Contact UsMay 2024

Hear from David Macholz, founder and CEO of the Advanced Vehicle Technology Group (AVTG)

Written by Eliza Gebb, Program Outreach Intern

For the past year, Vermont Clean Cities and Communities has been collaborating with the Advanced Vehicle Technology Group or AVTG, an organization dedicated to providing high-quality electric vehicle safety and first-responder training and reducing the knowledge gap around these vehicles. I recently had the opportunity to chat with the founder and CEO of AVTG, David Macholz, to learn more about the different training offerings and how AVTG came to exist.

As Macholz, who is based in Long Island, explained, he started AVTG in response to the increase in conversations around electrification, both the need for technician training and first responder training. There had been a couple of accidents in the Long Island area and Macholz noticed there was a lack of information surrounding the high-voltage systems and related to electric vehicle safety.

AVTG offers a variety of trainings at different levels. They offer a two-day electric vehicle essentials training, which covers awareness, safety, equipment, and more. They also offer three classes that build off each other: low-voltage electrical skills, electricity and electronics, and a high-voltage class specifically for technicians working on the high-voltage components within these systems. AVTG also offers training for automotive schools and technical training centers and several train-the-trainer courses. During the summer of 2024, they will be participating in two national events; first, a three-day train-the-trainer event as a part of a national conference organized by the National Institute for Automotive Service or ASE, the certifying body for the automotive industry. Then later this summer, the North American Council of Automotive Teachers or NACAT is also hosting an event where AVTG will be holding a three-day add-on training.

The AVTG’s courses have a variety of benefits, one of the major ones being increased safety. Transitioning from twelve-volt vehicles with few dangers for technicians to electric vehicles with upwards of eight hundred volts means there must be trained, capable technicians. Macholz also mentioned repair quality concerns – if these vehicles are not fixed properly, they can create a safety risk to their owners. It is crucial that technicians and first responders thus have a deep understanding of these vehicles and their many components, including the high-voltage and lithium-battery chemistries. As Macholz stated, “…the first folks that are often getting these electric vehicles are state agencies or government agencies where they haven’t historically had training plans; that’s where we come in, trying to assist them in not only training but also figuring out what professional development looks like long-term.”

AVTG’s training courses, and other electric vehicle training, also present the benefit for individuals in the workplace to be able to do more work on these vehicles. From the perspective of fleets working on or implementing these vehicles, their ability to fix them will be a cost-reduction in the long term. In the words of Macholz, “Once all these systems come to scale and there are a lot more electric vehicles, the idea of having just one person certified to work on them isn’t going to be sustainable.” Across the board, people are starting to realize the workforce component of EV training and the necessity of expanding the training opportunities available, however, it is crucial to continue to build awareness.

AVTG’s EV training courses also play an important role in terms of dispelling myths about electric vehicles. Macholz mentioned how one of the most rewarding aspects of his job is addressing concerns that arise regarding electric vehicle technologies and empowering people to adopt these vehicles. Macholz also enjoys teaching the high voltage class and said it’s “…new and different but it also has some parallels to what folks have done in the past. If they know how an alternator works, the electric motor is not very different; it just operates at a significantly higher voltage. I think the most exciting thing for us is working with technicians, and at the end of the day having the technician come up and say, this was amazing, we’ve learned a lot from this and feel good about this.”

In addition to discussing the training options and benefits, I also got to hear about Macholz’s current work as a Ph.D. student, where he is looking at the correlation between technician certification(s) and earning potential. As Macholz explained, there has never been a professional model for automotive technicians or licensing requirements. There is a certification model, however, certification within the industry is siloed. The median salary for technicians is low, and Macholz became interested in whether the number of certifications technicians have corresponds with how much they earn. He is relying on survey research to determine how many certifications someone might have, looking at equivalencies of those certifications across multiple certifying bodies, and finally analyzing the number of certifications in comparison to technicians’ annual income. Macholz’s research and work with the Advanced Vehicle Technology Group providing training and debunking myths about electric vehicles is crucial in our move to decarbonize transportation and build the corresponding workforce. To learn more about the AVTG and the various training courses offered, visit the AVTG’s website here.

April 2024

Food access and transportation with Ashley Bridge from The Vermont Foodbank

Written by Eliza Gebb, Program Outreach Intern

Food access is a major topic in Vermont, with USDA data from September of 2021 showing that 1 in 7 Vermonters struggle with hunger (Vermont Foodbank 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 in 3 Vermonters reported having experienced food insecurity at some point (Hunger Free Vermont, n.d.). Food access and transportation are intimately linked, one dependent on the other. Ashley Bridge, Community Food Access Manager at the Vermont Foodbank, is one individual working to connect the two in Vermont and increase food sovereignty and security. Bridge became interested in food access and related work while working for the New York Agricultural Stewardship Association (ASA) in Greenwich, NY.

The ASA received a grant to begin a gleaning program, or the harvesting of excess food to provide to those in need, with their local food access organization, Comfort Food Community. The gleaning program was a success due to the ASA’s relationships and connections with farmers and Comfort Food Community. The gleaning program was so successful that it spread further into the community, and other food pantries were also able to join. Bridge worked on the gleaning program for two years, during which the program grew to serve fifteen organizations. Her experience there catapulted her further into the realm of food access work. As Bridge states, “I loved seeing how something so simple could impact other peoples’ lives in a positive way, and so that’s what got me into food access and kept me going.”

The unique geography and context of Vermont create a variety of barriers to food access. One of the major barriers that Bridge and I discussed is money. People do not have enough money to buy the food they want or need, and they also do not have enough benefits, such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Another major barrier to food access in the state is transportation. Bridge mentions how “I work with people in Manchester, Vermont, and many of these individuals are New Americans who are new to the area and often don’t have cars. Shopping in Manchester is more expensive than shopping in Bennington, which means they have to travel on the bus to go down to Bennington to get much better prices on groceries. Transportation in rural areas can be tricky.” Finally, we also discussed the time factor, and how a lack of free time can be an obstacle and prevent people from being able to travel to obtain groceries or cook meals for themselves and their families.

Through her work with the Vermont Foodbank, a Vermont Clean Cities stakeholder, Bridge is helping combat these obstacles and create solutions to increase food access in Bennington County, Vermont. Bridge is a year and a half into a two-year project that involves collaborating with community members who access food through the Vermont Foodbank’s network partners, learning about their problems with food access, and engaging in generative solution-making with them. Bridge then approaches network partners or other community partners that might have an interest in or capacity for the solutions designed by the community members. All participating community members are paid for their time and treated as consultants, which helps ensure the program is valuing the community members and the information they share.

Bridge has enjoyed the two-year project thus far, stating that one of the most interesting parts is meeting with community members, listening to their ideas, and then working with them to implement their ideas. Thus far, the program has resulted in multiple food access projects and solutions. One of the projects involved bringing more prepared food to Bennington. To that end, the Vermont Foodbank collaborated with Grateful Hearts, an organization that gleans local produce from farms to create nutritious, delicious meals for community members. Grateful Hearts makes meals within one of the Vermont Foodbank’s community partner food pantries, providing around 1500 meals a week to community members. This collaboration with Grateful Hearts helped combat the lack of time previously mentioned. As Bridge explains, the partnership with Grateful Hearts “…really increased food, including prepared food, which helps many people who don’t have kitchens or people living in poverty who often struggle with not having enough time.”

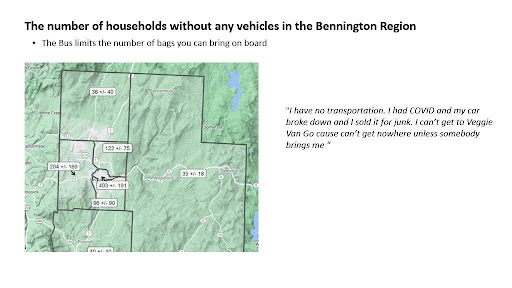

An additional project in collaboration with Net Zero Vermont’s Walk to Shop program also received funding. Through her work, Bridge learned that many individuals in Bennington walk to access food. Indeed, hundreds of Bennington area residents do not own or have access to a car, as the map below demonstrates:

Through her work, Bridge and the Vermont Foodbank secured funding to offer 150 walk-to-shop trolleys to different partner organizations in Bennington. The Walk to Shop trolleys have been a success and Bridge recently submitted a grant to buy 100 more for Manchester, Vermont. Currently, they are prioritizing individuals who do not have vehicles; however, they hope to distribute more in the future. Bridge was simultaneously able to make a connection to VeggieVanGo, a mobile food program run by the Vermont Foodbank that involves collaborating with healthcare sites and schools across Vermont to distribute fresh produce. Through working with and getting feedback from community members, the VeggieVanGo location was moved to downtown Bennington from where it had been before, far from the town center. Changes and projects such as these may seem small but can have a great impact on the day-to-day life of the individual.

Ashley Bridge, VTCCC, Net Zero Vermont, and Green Mountain Express staff members with Walk to Shop trolleys

Mobile food access and programs such as VeggieVanGo are crucial in today’s day and age and going forward. As Bridge states, “I have a fantasy that the transit system will also do mobile food access, that they will bring food to people, or have food at the bus station.” Bridge envisions a complete intertwining of the transit and food systems, in which there is a food pantry at the bus station, or a food-safe refrigerator, where individuals can access food. While this union of food and transportation is not the current reality, and there is much to be done to reach this vision, through the actions of individuals such as Ashley Bridge and organizations like the Vermont Foodbank working in collaboration with communities, this future is becoming less and less distant. If you would like to donate to the Vermont Foodbank, support innovative projects such as those mentioned, and help increase food sovereignty and security across Vermont, visit this link.

References:

“Household Food Security Report.” Vermont Foodbank, September 23, 2021. https://www.vtfoodbank.org/about-us/newsroom/household-food-security-report.

“Hunger in Vermont.” Hunger Free Vermont, n.d. https://www.hungerfreevt.org/hunger-in-vermont.

March 2024

In conversation with Aden Haji, founder of Haji Driving Academy

Written by Eliza Gebb, Program Outreach Intern

This March marks the one-year anniversary of Haji Driving Academy, a driving school located in Burlington, VT founded by Aden Haji. Haji Driving Academy aims to provide a quality driver’s education to individuals of all backgrounds, with an emphasis on language and cultural inclusivity, and safety. Haji Driving Academy has a variety of programs tailored to individuals of different ages and driving backgrounds, including one specifically for high school students. The Driving Academy has a partnership with the Vermont Student Assistance Corporation (VSAC), where individuals can apply for the VSAC Advancement Grant, and anyone 18+ who demonstrates need can receive funding to help cover the cost of driver’s education. This past January, I had the opportunity to meet with Aden Haji and chat about his experience opening Haji Driving Academy and the importance of driver’s education.

Interview questions and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity

What was your pathway to opening Haji Driving Academy?

I went to UVM, where I studied anthropology, and graduated in 2019. I first attended Castleton University for a year and then transferred to UVM because I realized that Burlington has a variety of opportunities for community involvement. Through the years, one consideration that has kept coming up is the importance of driver’s education and of getting a license. Having a license opens doors for people and brings families together. I had also helped some people through the process of getting their driver’s licenses and received some positive feedback, so that’s where the idea of Haji Driving Academy came from.

What are your major goals/objectives for opening and running Haji Driving Academy?

My primary goal is to provide a high-quality accessible driver’s education to individuals from all walks of life and create a safe and supportive environment with a focus on serving the needs of folks who are looking to get a formal driver’s education. It’s one thing to learn from a mentor or a family member but it’s also important to learn from an instructor who has gone through the formal certification process.

Fostering community engagement and promoting road safety continuously are also very important aspects of our mission. Working with community is one of the motivators that helped to open the driving school, and without that connection with community partners, the driving school wouldn’t exist.

What do you see as being some of the barriers to driving education and/or obtaining one’s driver’s license in Vermont, especially for New Americans?

Barriers to driving may include language barriers as well as having to navigate complicated, new traffic rules in English. “It’s already difficult to navigate this new culture, and then adding the complexity of traffic safety is a whole another experience, you know?”

Cultural differences in driving are another barrier, because, for example, someone may come from another country with totally different driving expectations and rules. I see a lot of clients who are used to driving on the opposite side of the road, and when they come to our driving school, we help them rewire their driving brains.

What do you see as necessary in Vermont to increase transportation equity and equitable mobility?

Achieving transportation equity and equitable mobility in Vermont requires a multi-faceted approach, including implementing language-inclusive driving education programs and improving public transportation infrastructure. It is also crucial to collaborate with community organizations, listen to, and work to bring communities together so there’s a voice behind what transportation can look like in Vermont, whether this means developing different workshops for community members and making sure that everyone is invited to the table. It is also crucial to advocate for policies that address the unique challenges faced by marginalized communities in accessing transportation.

What is your plan to incorporate any electric or plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in your driving academy?

Embracing sustainability is a key aspect of our driving school and our future. We plan on exploring partnerships with electric vehicle manufacturers and incorporating hybrid vehicles into our fleet. This aligns with our commitment to environmental responsibility and educating the next generation of drivers on the benefits and operation of eco-friendly vehicles. We emphasize and teach our clients the importance of eco-friendly driving. As a part of our driver’s education program, we use the AAA How to Drive Driver Program, which includes a section on electric vehicles and how to maintain and use electric vehicles. Going forward, I would also love to start holding community forums on eco-driving.

What is a challenging aspect of your job?

One of the most challenging aspects of my job is staying aware of evolving regulations and technology in the driving education sector and adapting our curriculum and methods to reflect the latest industry standards while ensuring the affordability and accessibility of our diverse student base. It’s important to me to make sure I am up to date because driver’s education and sustainable transportation are evolving every day, and it is both exciting but also challenging. Staying well informed on changes in rules and regulations can be difficult but it is also fascinating to compare the different policies in effect, including what is working and what is not, and examining the data that comes out each year regarding traffic, crashes, and more.

What is an interesting part of your job that you didn’t expect?

An interesting part of my job is witnessing the transformative journeys of our students and observing individuals gain confidence, overcome challenges, and eventually obtain their licenses. Their success is my success, as I like to tell them, and the sense of accomplishment and empowerment that they experience during this process reinforces the importance of our work at Haji Driving Academy. Another great part of my work is connecting anthropology with driver’s education; I interact with people from many different cultures, and individuals who speak a variety of languages. I have had a chance to meet folks from all over the world, from Thailand to Togo, South Africa, Kenya, Somalia, Brazil, Nepal, and more. I am thus able to learn about and experience many different cultures, and, as I tell people, it’s as if I am traveling the world without leaving the car.

February 2024

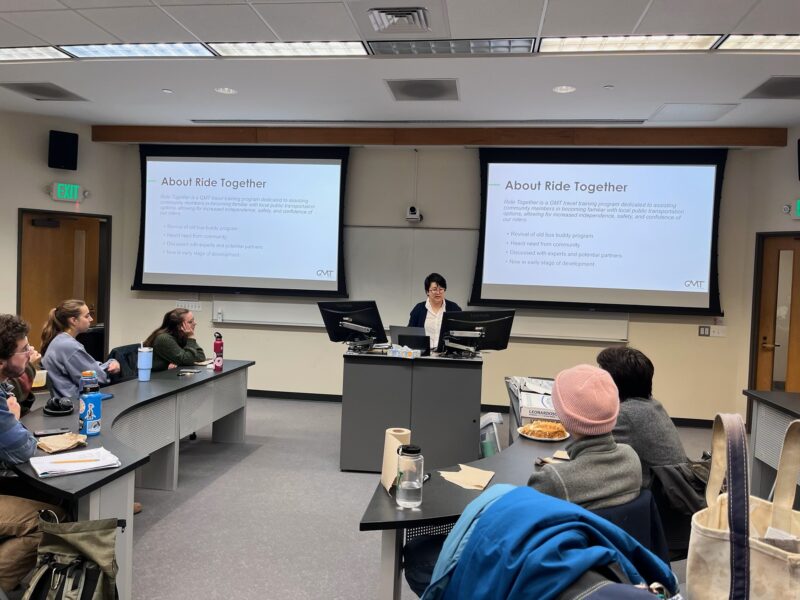

Irene Choi, Ride Together, and Green Mountain Transit

Written by Eliza Gebb, Program Outreach Intern

Green Mountain Transit (GMT) is launching a new travel training program in Chittenden County called Ride Together. I had the pleasure of meeting and chatting with the main face behind the new Ride Together program, Irene Choi. A recent graduate from UVM with degrees in Anthropology and Music, upon finishing her studies, Irene was drawn to Americorps to ease into postgrad life and help those in her surrounding community. As Irene explains, “I thought that Americorps would be a good opportunity for me to get my foot into the professional world and start working full time without having a set career path in mind and would also be a good opportunity for me to help people.”

As the GMT Americorps VISTA member, Irene has overseen qualitative data collection from GMT’s public ridership, mainly through visiting public stops in the area and obtaining feedback. Irene’s main role has been to create the up-and-coming travel training program Ride Together. While Burlington had a travel training program before the pandemic, it experienced minimal use and wasn’t well-maintained. For Irene, creating the new program has meant doing everything from conducting research on existing travel training programs across the country to gathering information through talking with potential community partners.

Ride Together is dedicated to teaching people how to ride the bus and encouraging people to take advantage of existing public transit infrastructure. The program consists of two parts, the first part is a workshop and includes a step-by-step overview of how riding the bus works. In the second part, trainees can ride the bus along with a supervisor so they can apply what they have learned in the classroom. Irene explains how one of the major advantages of the program is its flexibility; the program can be tailored to the needs of its participants, whether they would prefer a one-on-one training session or a group session. The field trip destinations are also customizable according to the needs of the individual. In the words of Irene, Ride Together is “…not designed to be a one-size-fits-all program.”

Irene is currently looking for volunteers to help carry out the training sessions and accompany trainees to ride the bus. The program has several incentives built in for volunteers. For every hour of volunteering, individuals will receive five days’ worth of free bus rides or approximately a $20 value. Trainees who complete both parts of the training, (the workshop and the onboard training), will receive one month’s worth of free bus credits, or a $50 value of bus credits (GMT’s monthly cap is $50). While individuals are welcome to take the training more than once, they are only eligible to receive the monthly bus pass once. GMT plans to monitor the program’s success using several methods, including complementary intake and post-training feedback forms, the up-and-coming Ride Ready app, and direct feedback.

Irene’s work on Ride Together is deeply linked to transportation equity. During our conversation, Irene stressed the importance of mobility and the ability to freely move from one location to another. As she states, “In the reality that we live in, it’s not so simple for everyone. We live in a very car-centric society, especially in Vermont, where it’s very rural.” With the Ride Together program, Irene and the GMT team hope to provide participants with the freedom to travel where they please and connect on a deeper level with the community they live in, opening doors for the people who need it the most.

Irene has enjoyed her time working with GMT and feels she has gained a new perspective on the Burlington community and the work that goes into maintaining a public transportation system. While at GMT, she has been able to develop a deeper understanding of public transportation and public service in general. After her year of service with Americorps, Irene hopes to attend graduate school for music. However, she would love to keep working for GMT in the future, whether it be related to travel training or not. As an Americorps, Irene has valued her work in public service and the opportunity to make a positive impact on the community she has grown to love. Thanks so much, Irene, for chatting, and hope you have a wonderful rest of your time as an Americorps member! For anyone interested in volunteering for Ride Together, or in being a trainee, feel free to visit the program website HERE or scan the QR code in the program flier above.

January 2024

Marshall Distel on all things CCRPC, urban planning, and transportation equity

Written by Eliza Gebb, Program Outreach Intern

The Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission (CCRPC) is one of eleven regional planning commissions in Vermont and the only federally designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) in the state. The organization’s overall objective is to plan for healthy and vibrant communities while furthering sustainable development, economic growth, and efficient transportation systems throughout the region. CCRPC has twenty-full time staff who work on projects involving energy, land use, water quality, transportation, and public engagement & equity, and collaborates with a wide array of groups and organizations, including: nonprofits such as Local Motion and CATMA, municipalities, state and federal partners, and schools.

I recently met with Marshall Distel from CCRPC to discuss his work there, the importance of urban planning, and the role CCRPC plays in fostering transportation equity in Vermont.

Interview questions and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity

How did you get involved in transportation planning?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been interested in planning and development and the way that cities grow and evolve, and I was first introduced to this concept of transportation planning at UVM as a student. I took this course called Sustainable Transportation Planning with Richard Watts. I think that course and Richard in general ignited my interest in transportation. I remember how we started out the course by defining transportation planning as developing policies, goals, and investments for, the future movement of people and goods, but the course also dove into the importance of realizing that it’s about more than just transportation. “Communities can shape our streets but our streets can also shape our communities and I think it’s critical for transportation planners to account for how our transportation systems have these physical, environmental, and socio-economic impacts on our communities.”

When did you start working at CCRPC? What does your role look like there?

I joined CCRPC back in 2014 as a summer intern. I was hired full-time as a transportation planner in 2015 after graduating from UVM with a degree in geography. In 2019, I received a master’s degree from Virginia Tech in Natural Resources with a focus on Global Sustainability. I was able to complete that degree by taking both in-person and online courses while still at the CCRPC. I took a couple of courses physically in India and in South Africa that focused on rapid urbanization, climate change, and economic inequality. That was an awesome experience and I’m super happy that I was able to continue working at CCRPC while doing that.

While I’ve been at CCRPC I’ve been involved in a wide array of projects and programs. I manage local and regional transportation studies, everything from roadways, intersections, park and ride studies, and bike and pedestrian facilities. I also manage the development of our annual work program and lead our public transit planning efforts in coordination with GMT. I’ve done some emergency management work, some water quality projects, some grant writing. There have been lots of other studies and projects over the years but that’s a comprehensive snapshot of the things I’ve done here.

Can you talk a little bit about the ECOS Plan and how it guides the work that CCRPC does?

Yeah, it’s an awesome plan. Since the 1970s we’ve been developing a regional plan that guides development and protects the county’s resources. We had been developing a separate transportation plan and a separate economic development plan, but then, in 2010 we received a million-dollar grant from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to rework those three separate plans into this one, comprehensive plan, the ECOS plan, which stands for Environment, Community, Opportunity, and Sustainability. This plan serves as the overarching framework for all of our planning efforts. We’re still updating one part of it right now, but we set goals and metrics and track data, including everything from vehicle miles traveled, walking and biking infrastructure developed, and ridership, and try to continue to further along those goals with our day-to-day work.

How does transportation equity fit into the ECOS Plan and your work at CCRPC?

Equity, and transportation equity specifically, is an essential part of the ECOS plan. We stress the importance of planning for walkable, vibrant, transit-oriented communities and have lots of goals and metrics concerning walking, biking, Green Mountain Transit (GMT), carpooling, and transit in the plan. I feel like transportation equity is all about ensuring that people, irrespective of age, race, ability, or socio-economic status, have a variety of options to be able to move throughout their community. It’s important to realize how detrimental it can be for communities to be developed so they’re dependent on cars.

“I think that sprawling, single-use, low-density patterns of development inflict so many negative consequences related to the economy, health, environmental impacts, and I think that our work at CCRPC is committed to supporting this idea of a multi-modal transportation system that works for everyone.”

What role do urban planning and CCRPC as an organization play in furthering transportation equity in Vermont?

I think one thing specifically that planning organizations need to do to further transportation equity is continue to work to unsilo this transportation and land use nexus. You can advocate for transit and walking and biking all you want but if communities continue to grow this low-density pattern of development it’s not going to achieve any of our transportation equity goals so we can continue to advance initiatives that support developing compact communities and housing in our downtowns and villages rather than pushing development outward.

How do you balance transportation equity and infrastructure projects?

That’s one of the main concepts that transportation planners have to contend with; this idea of mobility versus livability and finding a balance between moving people and goods, and providing a system that supports equitable community development, public health, social inclusion, and sustaining the environment. So, with every planning study, we consider all mobility needs. For example, we recently completed this study that focused on I-89, and developed a vision, goals, and objectives that will guide how the interstate corridor will evolve over the next thirty years and, even though that was an interstate focused study, one of the outcomes was the need to develop a transportation demand management (TDM) plan, to help us identify opportunities to avoid making those costly investments in infrastructure on the interstate. And instead, if we make those investments in transit, in active transportation and carpooling, we may be able to reduce traffic congestion and therefore, reduce the need to do something like widen the interstate.

What are some of the challenges of your job?

I think that working for a regional form of government, community and stakeholder collaboration is what’s needed to make meaningful change. That can be challenging, to get everyone on the same page and move forward with this unified vision. I think stakeholder collaboration is a big part of what CCRPC strives to achieve. When you have these isolated efforts by individual entities or organizations it’s often ineffective and to get that meaningful impact requires the coordination of all these different stakeholders addressing an underlying issue. So, while it’s sometimes challenging to work with all those folks, I think we work hard to bring together federal and state and local partners to address the local challenges that we face.

What is a surprising part of your job that you didn’t expect?

There’s a lot of interesting work at CCRPC. Zoning is something that I have become pretty interested in and it is definitely not something that was on my radar when I was first starting out as a transportation planner. I’m passionate about working to support walkable communities. I think strong and vibrant downtowns attract people, investment, and opportunities, and it is central for a community’s economic health and livability to have these walkable, vibrant downtowns. That said, I think I’ve come to realize that zoning has been one of the biggest barriers to building these types of communities that are walkable and transit ready. We’ve got these massively complex zoning codes, some adopted many decades ago, that are blocking this type of development, and…

“…in a number of our communities, zoning has left places to be increasingly unaffordable, stagnant, segregated, sprawling. It’s chipping away at the health of our communities and environments; I’m a big proponent of overhauling zoning and it was not something I was even thinking about when I was just starting as a transportation planner.”

If you go to some local municipalities and look at their zoning codes, it’s two hundred pages of rules and regulations that are promoting sprawl and preventing smart growth and compact development. It’s crazy to think that some of the most vibrant, amazing places that we have in this country were built before zoning, and if you were to try to build those places again right now with current zoning codes it would be illegal. That seems like a bit of a problem. At CCRPC we’ve got land use staff that are working with communities to make adjustments to zoning to allow for more walkable development, reducing things like parking minimums and minimum lot sizes which prevents infill development. And there’s lots of changes happening state-wide and in the legislature to address zoning, not just in Chittenden County but across the board, which I’m super excited about.

September 2023

Learning From Leif Maynard, a Young Climate Policy Implementation Fellow at the U.S. Department of Energy

Written by Hanna Hartman, Program Outreach Intern

Leif Maynard is a friend of mine from our time at Amherst Regional High School in Massachusetts. When I saw that he was as an ORISE Fellow at the U.S. Department of Energy, I reached out to learn more about his personal journey in the environment, equity, and public policy to help ensure a just energy transition to reduce and avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis. Through Leif, I learned that the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant (EECBG) Program can help Vermont communities move towards decarbonization in a way that centers place-based strategies and climate justice. The EECBG Formula Grant Program is offering $430 Million in funding for eligible state, local, and Tribal governments. Vermont’s state government has $1,594,420 available through the grant and an additional sum of $1,520,120 has been allocated to ten eligible local governments.

For Leif, the issues of equity and environmental action have been “very intertwined” throughout his path to working on federal climate policy implementation. After graduating from Bowdoin College this past spring Magna cum Laude, Leif secured a position as an ORISE Communications and Stakeholder Engagement Fellow in the Office of State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP) within the U.S. Department of Energy. We spoke during his fourth week on the job, where he is working on the EECBG Program team.

At Bowdoin, Leif double majored in Environmental Studies and Government & Legal Studies, with a minor in Hispanic Studies. Leif has always been “professionally, personally, and politically interested in climate change and environmental action.” During his time as an undergraduate, he investigated “how questions of power fit within an environmental frame.” Much of his previous research, internships, and work has related to “what a just energy transition can mean in rural New England.”

Leif is hoping to support a transition to renewable energy throughout the country as “someone who grew up in rural Western Massachusetts and feels deeply committed to supporting the ecological livelihoods of rural places that are increasingly facing challenges from the climate crisis and risk being lost.” He accepted the yearlong fellowship, sponsored by the Oak Ridge Institute of Science and Education, to understand how federal policymaking works. Policymaking is important to understanding the flow of money from federal programs to smaller entities, and to learn how local partners can become more empowered to serve their communities through engagement with the federal government.

The Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant program is currently funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 (commonly known as the Bi-Partisan Infrastructure Law) and “offers resources to local governments, states, tribes, and territories to lower energy costs, reduce carbon emissions, improve energy efficiency, and reduce overall energy use.” Leif underscored the urgent importance of reducing emissions across the country to meet local and national climate goals and avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Funding from the EECBG program could be used to:

- Retain consulting services to create a climate action plan,

- Electrify municipal fleets and install EV charging stations,

- Establish an energy retrofit program for low-income communities,

- Install solar and battery storage on a government building,

- Build out safe biking infrastructure.

Find complete guidance on the many eligible uses for EECBG Program funds here.

Leif explained that the grant focuses on place-based clean energy strategies and hopes that it will support local governments “to launch creative climate change mitigation projects that makes sense for their communities.”

Additionally, SCEP is accepting applications for a new technical assistance program, the Community Energy Fellowship. The program will place 25-35 recent college graduates and young professionals to support eligible local governments and Tribes with their EECBG Program projects. These Fellows will bring new expertise and perspectives to local communities and accelerate the transition to resilient and affordable clean energy.

Leif thinks “this program will help local governments respond to this crucial moment” for decarbonization and “implement these projects in a creative way with a fresh set of eyes and more support on the ground.” The fellowship will bolster the clean energy workforce and hopefully employ people with a connection to the communities hosting Fellows.

In Vermont, there are twenty local governments eligible for EECBG Formula Program funding: Bennington, Brattleboro, Burlington, Colchester, Essex, Hartford, Milton, Rutland, South Burlington, and Williston, as well as Addison, Caledonia, Chittenden, Franklin, Orange, Orleans, Rutland, Washington, Windham, and Windsor counties. Leif explained that of these municipalities, only governments applying for traditional grants (not equipment rebates or technical assistance vouchers) are eligible to apply to host Fellows. If a municipality receives a Fellow, they can share the Fellow’s work capacity with other municipalities in the region that are receiving EECBG Program funding. He underscored that “it could be really worthwhile, especially for rural communities with limited administrative capacity.”

About Leif—how a young environmental activist enters a federal policy fellowship.

Leif is excited that this new position “ties into my previous work and my lived experience in rural New England.” We both grew up in the Connecticut River Valley of Western Massachusetts. Leif reflected on the Valley as a place intertwined with its natural environment. “You saw it every day and you were in it—not just the forests and untouched nature—but also small farms and networks of people who are tied to the place in a meaningful way and making their livelihoods from it,” he said.

As his understanding of the world grew, he got involved in politics and activism. He emphasized that “through exercises of power, different communities can build ecological futures and strive for the good life in those places, whatever that means for them.”

In college, Leif was a co-leader of the Bowdoin Sunrise Movement, as well as a Bowdoin Votes Democracy Ambassador. “I hope to see more people involved in activism and advocacy at our age” learning through the kind of work we’re doing to “navigate structures of political power and the policymaking process to get resources to local communities for climate action.”

Leif took an “amazing” class in the Environmental Studies department, Talking with Farmers and Fishermen, a social science research methods class with Dr. Shana Starobin. He was able to interview farmers and fisherman “about their concerns surrounding rural livelihoods and renewable energy development.” Through the class, he made sense of “the complex relationship of energy and food systems that exists in rural New England and other regions around the world.”

Leif argued that understanding environmental history in North America, a required topic in Bowdoin’s environmental studies program curriculum, is crucial to “navigating the nuance of how people are responding to environmental and climate questions across the country and meeting diverse community needs,” as political context and material conditions are grounded in history.

Leif studied abroad in Ecuador his junior year with the School for International Training (SIT), a global institute of higher education and social justice headquartered in Brattleboro. For the last month of the semester, he worked on an independent project with the environmental justice collective Yasunidxs Guapondelig to understand environmental activism and just ecological transitions from the perspective of communities resisting mining projects Cuenca, Ecuador. One of Leif’s most important takeaways from this experience was that “we need solidarity in the global network of environmental grassroots activism” and to learn from each other’s frameworks on climate justice.

In the Summer of 2022, Leif worked on policy analysis and green financing programs through an internship with Coastal Enterprises, Inc., a community development financial institution (CDFI) in Brunswick, ME. The work, including collaboration on grant proposals totaling over $450,000 to expand environmental lending programs for small businesses and farms, showed “the power of targeted funding to directly shape climate action and to make an impact in local communities.”

As someone who is unwaveringly passionate about climate justice, equity, activism, and the transition to renewable energy, Leif Maynard is a valuable addition to the Department of Energy. His interdisciplinary academic and professional background will provide a fresh and relevant viewpoint reflecting the next generation of environmental professionals who are critical to creating an inclusive network of empowered rural communities throughout the country. I am excited to follow the work he does as a Fellow this coming year.

August 2023

By Hanna Hartman – VTCCC Outreach Intern

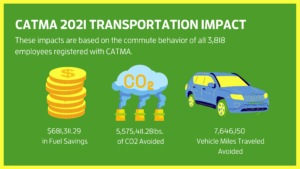

Last week, I sat down with CATMA (Chittenden Area Transportation Management Association) to discuss the new bikeshare system in the greater Burlington area. Bird offers electric bikes (e-bikes) to our community. I spoke with Katie Martin, Associate Director, and Marlena Compton, Senior Marketing Associate, to learn the ins and outs of the program.

CATMA partnered with Bolt Mobility for the Greenride Bikeshare program until the Summer of 2022, when the company unexpectedly went out of business. Over the past year, CATMA has been overwhelmed with feedback that community members wanted another bikeshare. A Community Bikeshare Survey open in Winter 2022 received more than 1400 responses, with “over 75% of respondents agreeing that the system should rebooted.”

CATMA has worked incredibly hard to get bikeshare out on the streets this summer. Throughout the last year, the organization has juggled a community survey and a request for proposals, finally negotiating contracts with the cities of Winooski, South Burlington, and Burlington, as well as Bird.

The transportation management association is excited to return 200 e-bikes to the Burlington area. “It is very satisfying to be able to give people what they obviously want,” Marlena said.

Bird functions differently from the previous bike share, so CATMA is focused on educating people on how to use and park the bikes properly. Instead of a bikeshare system where users must return bikes to a designated hub, Katie explained that Bird bikes “move around the community in a way that’s more accessible” to more neighborhoods. Bird bikes may be parked responsibly on the edges of sidewalks or at bike racks. With the previous docked system, residents of the Burlington area who lived outside of the downtown core did not have access to bikeshare near their homes.

Marlena reported that there are now bikes throughout the area, including at the bus shelter near her home in South Burlington, as a bike rack isn’t required to park the bikes. This example shows that the bikeshare is helping to boost personal mobility and create another option for the last mile of daily transportation.

Jeremy Lynch, a Senior Government Partnerships Manager at Bird, explained that the battery of the bikes is swappable, so “local Fleet Managers can easily change out the batteries while keeping the bikes on the street and available for use 24/7.” Fleet Managers charge the batteries at facilities with standard electrical outlets. A full battery will last between 40 and 50 miles.

There are no gears on the bikes, as it is fully electric. The rider’s pedaling engages the battery and boosts the power of the rider’s exertion to a speed of 15 mph, at which point the battery stops assisting.

The seat can be adjusted, with a maximum weight limit of about 300 pounds. The bike is very sturdy at 70 pounds and balances easily. The front basket is attached to the frame instead of the handlebars, providing “a better center of gravity for the rider and helps with balance on tighter turns.”

Marlena pointed out that e-bikes “make biking more accessible for a larger number of people.” As part of a one-car family, she uses the bikes to go to the grocery store, as the distance is a bit much to walk from her house. CATMA has access to data on where people use the bikes. Marlena explained that “people are taking them into the city from outside, getting to sports events and getting to work.” I have used the bikes to get home up the hill from the waterfront and with friends visiting from out of town.

Birds cannot be ridden or parked on Church Street Marketplace or parts of Champlain College Campus. The bikes automatically reduce their maximum speed at the UVM Medical Center campus, the downtown Waterfront, and parts of the University of Vermont campus, with parking restrictions detailed in the Bird app. Bikes are also forbidden at Red Rocks Park, and Parks & Recreation land in the City of Winooski.

A well parked Bird.

Katie disclosed that if community members, organizations, or student groups are interested in seeing data from the bikeshare, that is something that CATMA can provide through their contract with Bird. Marlena expressed that access to data “creates more opportunities for us as a community.” As a metropolitan area committed to sustainable transportation, this data can help show which neighborhoods could benefit from additional transit, bike, and pedestrian infrastructure.

Emily Adams, CATMA’s new Program Analyst, shared some of this data with me.

This graph shows the average number of BIRDS available for use in the public right of way (PROW) and the number of rides each day.

The heat maps of bike ride start and end locations “look nearly identical, but something fun to note is that many people are using the bikes to end their trip around the beaches off the bike path,” Emily explained.

By allowing riders to choose exactly where their trip starts and ends, Katie expressed that “the users get more involvement in the system.” She wants bikeshare users to “be good users because it’s your system” and that by parking bikes appropriately, they avoid affecting other community members negatively.

It is most effective and time efficient to report broken and improperly parked Birds by emailing vermont311@bird.co, as there is no phone number hotline. Marlena pointed out that “there are fleet managers in Burlington managing the bikes, and they are very eager to pick up abandoned bikes because nobody wants them where they shouldn’t be.”

The bikes cost one dollar to unlock and 0.49 cents per minute of riding. CATMA members are eligible for a 20% discount, and Bird offers Community Pricing, which is a 50% discount for “senior citizens, U.S. veterans, and individuals participating in a state or federal assistance program.” CATMA encourages organizations working with these populations to highlight the Community pricing model.

In the Bird app, you can find a promo to send a friend a free ride. After they take a Bird for a spin, users will receive a free ride for themselves. Bird is ideal for point-to-point trips under 30 minutes. For longer bike rides, contact local bike shops for rental prices.

Katie affirmed that if CATMA finds that local Bird users need a more accessible pricing model, they will work with Bird to evolve membership plans to “fit the needs of our community.” Throughout the country, Bird offers a per-trip model of pricing. Still, CATMA will work through the winter to evolve pricing options and hopes there will be a monthly or yearly plan in the next biking season.

I want to recognize CATMA’s persistence and dedication in bringing bikeshare back. As the biking season progresses, the organization is analyzing the data and workshopping the initial system we have today to make a bikeshare that works for everyone. Check out their Bikeshare FAQ for more information on the bikes. If community members have feedback on the bikes, please send your comments to CATMA by emailing info@catmavt.org.

July 2023

By Hanna Hartman – VTCCC Outreach Intern

CCE Golf Cars Opens New Location in South Burlington

CCE Golf Cars is the nation’s largest distributor of small-wheeled electric vehicles. While connecting with the company at VTCCC’s Green Your Fleet event, we learned about their new location in South Burlington. I talked to Chase Newton, the Director of Marketing and Business Development at CCE, to learn more about the company’s customer base and upcoming opportunities in Vermont.

Founded in 1978, Country Club Enterprises (CCE) focused on being Clubcar’s New England fleet partner for over 40 years. When small-wheeled electric vehicles emerged in the market, CCE realized they could take advantage of that space. Chase aims to grow the consumer and commercial small EV market by helping municipal, residential, commercial, and institutional customers go towards a “greener future” by replacing aging internal combustion engine vehicles.

The marketing department is new at CCE Golf Cars. Chase Newton joined the team with the new CEO, Peter O’Connell, in December 2022. He focuses on experiential marketing by holding events to “put people behind the wheel of electric golf cars,” as CCE offers a product unfamiliar to most consumers.

CCE is excited to engage with customers at their new location in South Burlington at 2041 Williston Road. The company took over from John Thompson’s Golf Cars in June of 2022, and fully renovated for a fresh start as the fifth location of CCE Golf Cars in New England. Additionally, the company’s CEO and CFO, Russell Spencer, are UVM alumni, so they are looking forward to having more opportunities to visit the area. CCE aims to “maintain the relationships and reputation that [they have] come to earn over all these years [in New England],” said Chase.

Small-wheeled electric vehicles include models from companies including Club Car, Onward, Garia, and GEM. CCE Golf Cars is the only New England dealer for GEM vehicles. Electric golf cars are quiet, reducing noise pollution on college campuses, neighborhoods, and golf courses that have switched from similar gas-powered vehicles.

In addition to taking care of the long-term partnerships with golf courses in New England, CCE serves the consumer and commercial markets. For the consumer market, Chase explained that their “focus is on fun,” providing cars with special features such as lift kits, sound systems, cool colors, and rims. Part of this market is the campground audience, who can use the vehicles to get the family to the lake and back. The manager of the South Burlington store, Jerry Wadsworth, explained that many campgrounds in Vermont will require campers to use electric golf cars in the future.

“The new and growing space in consumer markets are low-speed vehicles,” said Chase. Some models of small-wheeled electric vehicles are street-legal on roads in Vermont with a speed limit of 35 mph or less. With zero tailpipe emissions, these vehicles are great alternatives to internal combustion vehicles for customers looking to save on the environmental impacts and economic costs of their transportation. Due to slow speed limits in many Vermont population centers, including Burlington, street legal options such as GEM’s 2022 ELXD and Garia’s 2023 Via make it possible to get around town with zero tailpipe emissions.

Commercially, CEE is “really eager to push environmentally conscious fleets on campuses” to assist colleges and universities in fulfilling their sustainability initiatives and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Campuses can utilize CCE’s small, reliable alternatives in maintenance fleets, athletic departments, and other on-campus uses.

At Wake Robin in Shelburne, VT, the maintenance team uses the Club Car 2023 Carryall 500 with the turf package, which they purchased from CCE Golf Cars in the winter of 2022. Leslie Parker, the Director of Environmental Services, explained that Wake Robin replaced a gas-powered golf cart with the electric model, which is easy to charge on regular outlets with Level 1 charging. As the maintenance team only works during the day, charging logistics are “not an issue.” The primary advantage of the golf car over other electric vehicles in maintenance work is that they are All-Terrain-Vehicles and “can be driven over the lawns without concern for damages to irrigation or geothermal wells from the weight of the vehicle.” For the grounds team, the Carryall 500 works great in warmer weather to move items such as tools, ladders, and plywood, replacing a pick-up truck for many tasks.

Here in Burlington, the Vermont Lake Monsters baseball team use an electric golf cart, which they replaced with the help of incentives from the Burlington Electric Department. Their mascot Champ loves driving around in an energy efficient EV.

As most vehicles are open-air, CCE’s “bread and butter are the spring, summer, and fall.” Although the range and run time for small-wheeled electric vehicles vary by make and model, GEM’s lithium battery vehicle has a 90-mile range. At CCE Golf Cars, the pre-owned electric vehicles range from $4,995 to $12,495. While often being more expensive up-front than gas-powered cars, EVs require less maintenance and are powered by electricity with stable prices, leading to long-term savings. Many pre-owned electric fleet cars– CCE’s best sellers– are upgraded Club Cars sourced from retired golf fleets. They are customizable with various sizes, colors, lifts, and stereo options. CCE has over 450 pre-owned electric vehicles in inventory.

Sustainability is a high priority for CCE Golf Cars. Chase asserted that “there’s a reason why we are selling mostly electric vehicles: we see it as the future.” Furthermore, he predicts that the ban on petroleum-fueled small-engine in California will spread throughout the country and become the standard. CCE is “proud to offer alternatives for all types of vehicles,” from college clients to campground-loving families. If you’re interested in trying out an electric golf car, head down to CCE in South Burlington for a test drive with Head of Sales Tim Martell.

May 2023

By Cate MacDonald – VTCCC Outreach Intern

Walk to Shop

I recently sat down with David Brantley, a Senior at the University of Vermont who works in the Office of Sustainability. In fall 2022, David was awarded funding through UVM’s Sustainable Campus Fund (SCF) for the purchase of Walk to Shop Trolleys. The SCF supports student-led sustainability projects that make necessary changes to reduce the University’s impact on climate and the environment.

With the grant funding, David partnered with Walk to Shop, a non-profit program that offers shopping trolleys at cost – or fully subsidized to many Vermonters – to help them carry goods more easily. David wanted to bring the Walk to Shop trollies to the residence halls at UVM. Pictured to the right, these lime green trollies provide an easy way to carry groceries while walking or using public transportation. The tolly is light, maneuverable, and rolls smoothly over sidewalks and interventions. Additionally, its vibrant color is highly visible for safety.

The Walk to Shop program seeks to support more efficient travel for necessary short trips by walking instead of driving to destinations. Most Burlington residents live within a 15-minute walk of their nearest grocery store, though many are unaware of this. The trolley serves as an important accessibility tool allowing a greater range of people to make these short shopping trips by walking.

David shares his lived experience which prompted him to bring the trollies to campus for student use. Growing up in Tennessee, David had never ridden transit before. When he arrived at UVM, he did not have a personal vehicle. David explains the logistical and financial complications that occur when every college student has a car. He thought, “I’m just not going to deal with it. I want to experiment a little bit.” David navigated without a car very smoothly until moving off campus. He explains the experience of carrying heavy grocery bags back to his apartment. He attempted putting them on his bike but quickly discovered that was not an easy solution when navigating the hills in Burlington.

In September, David went to World Car Free Day, an event at City Hall Park that aims to highlight opportunities available to live car-free in Burlington by walking, biking, and using public transportation. At the event, David encountered Walk to Shop for the first time and immediately saw the trolley as a practical, affordable solution to his problem. David explains, “People wouldn’t bat an eye spending the same amount or more to repair their car, buy a tank of gas, or purchase a parking pass.” The Walk to Shop trolley eliminates the need for these other spendings. David wanted other students, both on and off campus, to have the trollies as a resource to ease the difficulties of walking or taking the bus to shop.

David partnered with the Walk to Shop team along with Caylin McCamp and Abby Bleything from the Office of Sustainability to apply for UVM’s Sustainable Campus Fund. With the funding, David purchased 25 trollies from Walk to Shop, distributing two to each of the 11 Residential Life desks and two to the Hoffman Desk on the first floor of the Davis Student Center to be available to all UVM students and staff. And one is located in the Office of Sustainability. David reports that the trolleys are being checked out by a handful of students and staff. Most people are using them for food and cleaning supplies. David states, “There are a lot of practical uses for it. I’ve used it for grocery shopping, the farmers market, club things, and one time I put a pumpkin in it!”

Posters are distributed around campus promoting the trollies. David created a menu of things that are offered at the Residential Life desks and the Hoffman Desk in the David Center for UVM students and staffs’ convenience, including the Walk to Shop trollies. Outreach has also occurred through social media, peer-to-peer conversation, and events such as a trolley painting event on UVM’s Trinity Campus.

Posters are distributed around campus promoting the trollies. David created a menu of things that are offered at the Residential Life desks and the Hoffman Desk in the David Center for UVM students and staffs’ convenience, including the Walk to Shop trollies. Outreach has also occurred through social media, peer-to-peer conversation, and events such as a trolley painting event on UVM’s Trinity Campus.

The Walk to Shop program is well equipped to continue into the future as UVM Residential Life signed onto the project and will continue to manage the trollies after David graduates this spring.

Thanks to David for launching this project at the University of Vermont. This is a huge step in the right direction to introduce UVM students to the ease of carrying goods with the trolley, using public transportation, making Burlington a more walkable city, and reducing the need for personal vehicles!

David concluded our conversation by talking about his car-free lifestyle. He describes the bus as originally being challenging and intimidating, though in only a couple of weeks riding it, he felt comfortable navigating the city. David states, “I started thinking about the sustainability aspect. It started to make less sense to drive price wise and environmental impact wise.” When asked to provide advice to people exploring a car-free lifestyle, David states, “Start a little bit at a time and carve out time to get comfortable with it. You will build confidence. College is the perfect place to try new ways of moving yourself around!”

April 2023

By Cate MacDonald – VTCCC Outreach Intern

CarShare Vermont

CarShare Vermont is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to provide an affordable, convenient, and reliable alternative to private car ownership that enhances the environmental, economic, and social wellbeing of our community and planet. CarShare has a network of vehicles parked in convenient locations around Burlington that members can reserve and use by the hour or day wherever they need to drive.

Last week I sat down with Alicia Taylor, CarShare’s Director of Community Engagement to learn about CarShare Vermont’s mission and how it has impacted Burlington and surrounding communities for the better. Alicia joined CarShare’s team in 2012, four years after the nonprofit was established. At the time, the organization had about 10 vehicles and 500 members. Alicia is proud to say that today, CarShare Vermont has over 1,000 members and 22 vehicles and counting.

Reducing emissions and improving mobility

Transportation is one of the biggest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the state of Vermont and driving personal vehicles is the largest segment of that. When people have cars parked in their driveways, they are convenient, causing them to drive their vehicle way more than it needs to be driven. CarShare is on a mission to help people own less vehicles, causing people to be more mindful and naturally drive less. Whether that be a two-car household going down to one, or being car free altogether, CarShare is providing people with a way to reduce their carbon footprint.

With currently 50 percent of its fleet either fully electric or plug-in-hybrid, CarShare is working towards electrifying its remaining plug-in-hybrids, bringing two more dedicated chargers online this year. CarShare’s plug-in hybrid vehicles allow members to drive 25 fully electric miles – and luckily for them, most CarShare trips are within 25 miles!

Because members have varying levels of experience and knowledge with hybrid and electric vehicles, CarShare’s Go Electric video helps to demystify the different types of EVs in their fleet. Alicia states, “you don’t have to be nervous; they are easy to use!”

Shifting behavior: Park-It-Pledge campaign

CarShare’s Park-It-Pledge campaign is a great way for people to experiment with a car free lifestyle. By committing to “park” their car for two months, driving it as little as possible, pledgers receive a bus pass, bike incentives, and a CarShare free trial. By changing mobility practices, pledgers can see that a car free lifestyle is possible and they can use that knowledge and experience to continue that behavior change.

Alicia highlights the efficiency of CarShare, stating, “For me, if I am booking a car, I am usually doing two to three errands at a time. Trip chaining is a much more efficient use of cars.”

CarShare membership and membership options

Alicia emphasizes that Carshare is for everyone. Membership options range from college students that cannot bring a car to campus but may want to go to the mountains for the day, to seniors in affordable senior housing that are ready to not own a vehicle anymore but still want the independence and freedom of having access to a car. And everyone in-between! Alicia shares that in her household with young kids in Burlington, they do not need to own a car because they can walk, bike, or take the bus to school and work. Through CarShare, they are still able to travel out of town for other activities. CarShare allows them the opportunity to not spend money on a vehicle that is ultimately losing value.

CarShare’s Mobility Share plan offers financial assistance for low-income households. The plan offers discounted driving rates and waives the membership fee entirely.

Other membership plans are geared toward college students and staff, businesses, individuals, and households. Read more about pricing and membership options at carsharevt.org.

Be Car Conscious Cost-to-Drive Calculator

How much do you think it costs to operate your primary vehicle for one year? CarShare Vermont recently launched its Be Car Conscious Cost-to-Drive Calculator, a tool to help Vermonters get a sense of how much it really costs to own and drive a car. To be more conscious of your true driving costs, calculate here!

Future Plans

This spring, CarShare VT will be expanding to Winooski, bringing two vehicles with the help of state funding. CarShare is excited to work with the state to show that car sharing is very valuable and could be a model for other communities. Car sharing can have big impacts on communities like Winooski, allowing households that do not have cars mobility for the first time.

Because Vermont is considered rural carsharing, there aren’t a lot of models like it in the country. CarShare VT proves that car sharing can have a huge impact on people’s lives and their ability to access the services that they need to get around. But it does need some state support, just like public transit, to expand services into new areas. Alicia emphasizes that CarShare VT is open to sharing resources, knowledge, and expertise to help expand car sharing and other shared mobility options. There is a lot more growth possible here in Burlington and surrounding areas.

November 2022

By Maisie Melican – VTCCC Outreach Intern

Propane as a Renewable Fuel

Judy Taraovich from Proctor Gas

As we transition heavy-duty vehicles away from diesel, alternative fuels renewables and biofuels are important to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve air quality, and save Vermonters money. Vermont Clean Cities Coalition works locally to advance and increase the use of domestic alternative fuels, and their renewable options, all of which reduce petroleum consumption and the emissions that impact our air quality. This interview with Judy Taraovich from Proctor Gas will help explain more about propane, renewable propane, resiliency, and reducing emissions.

Proctor Gas was formed in 1966 by the Taraovich family. Jimmy, Judy’s husband, took over the family business in the mid-80s. When he passed away in 2010 after a motorcycle accident, Judy was running a gift shop alongside the existing Hearth store and was not very involved in the management of the propane business. After the accident, she recalls gathering the team together and asking them what they wanted to do. She said, “I can sell it today and we’ll be okay, or we can stay together. We’ve been a family for a long time, and we can move forward, if we do that, you have to understand that you’re all babysitters until I can learn.” They decided to stay together, and Judy started running the company on her own in October of 2010. It could never have been done without great people, she says.

It took Judy awhile to get the hang of the propane industry, something she says is an ongoing process. Renewable fuels are evolving at an incredible rate right now. We’re growing to meet the demand, Judy says, especially with the renewable piece, we’re answering the call. Propane is the third most popular vehicle fuel worldwide, but the US has been slow to embrace it because gasoline is so readily available. Many people don’t want to rely on gasoline and diesel as much, and they’re thinking electric is their only alternative, and that’s not the case. Others are pushing back on electric cars. They want what they know, and with a gas station on every corner, people don’t want to be limited to where they can find fuel.

Although propane autogas isn’t as popular as gas or diesel in the United States, school buses and transit buses have been using the alternative fuel for a long time. According to the Alternative Fuels Data Center, propane autogas was first considered an alternative green fuel under the Energy Policy Act of 1992. The decision was based on its clean burning qualities, domestic availability, and comparatively low costs, all of which make it a viable alternative to more traditional fuels. That’s what they use in Maine at Acadia National Park, Judy notes, because propane is much safer than diesel for the park’s ecosystem. They began service in 1999, and after 20 years of service, they added 21 new propane busy to meet the demands of the busy park.

As an industry, there continues to be a lot of research into getting propane auto gas off the ground. They’re doing a better job of getting the word out and saying, “we’re not only a viable option, but for energy security and for clean emissions, we need a seat at the table.” Propane is very low in CO2 (Carbon Dioxide), NOx (Nitrogen Oxides), and SOx (Sulfur Oxides) emissions. It’s a clean burning fuel, it’s much friendlier on engines, and it’s very portable. It can easily be added as a fueling station alongside a regular gas station, and the fill time is the same as filling your gas tank.

Another benefit is that propane boils at – 44º, it doesn’t matter how cold we get in Vermont, your propane engine will start in the morning. During disasters, like the freeze that happened in Texas last year, they relied on the propane school buses to transport residents to safety, as it was the only fuel available to move people around. This is why it’s important to diversify the U.S. fuel supply, especially with domestically produced fuels that use established infrastructure. Overall, propane reduces our use of imported petroleum and strengthens national security (AFDC). When the VW money became available, Judy lobbied to get a propane bus to demo in Vermont. Even though they were supposed to use alternate fuels, they focused primarily on electric. You can buy two and a half propane buses for the same price as one electric bus, Judy says, taxpayers would have had more buses for the same amount of money. Right now, although propane pricing has gone up, it’s nowhere near other fuels and remains stable. According to the July 2022 Alternative Fuel Price Report, propane autogas in New England is $3.78 a gallon, compared to $4.54 for regular gasoline (see page 14).

Propane has a lot of good properties, and as we move to renewable propane, we can be net zero emissions. Renewable is the exact same chemical makeup as regular propane, C3H8, so 3 carbons and 8 hydrocarbons, explains Judy (AFDC). It comes from waste materials, such as animal waste, recycled garbage, and cooking oil. Although there’s a lot of different feed stocks, it still has the same carbon intensity whether it’s renewable or regular propane.

Judy had a renewable propane event at the end of June and received inquiries from a variety of people. I don’t think it would be a hard sell, she says, it’s just a matter of selling something that I can’t provide yet. There’s not enough of it in the East right now, most renewable propane is coming from Louisiana. They’re upping production, they know the industry needs it, so the research and the move is a lot quicker than it was five years ago. The reality is that we’re not ready to supply renewable to every costumer, but it’s the same situation with electric. I have been and continue to be a firm believer in balance, Judy says, all energies still need a seat at the table for energy security.

Having talked to the Vermont legislature and testified at the Energy Committee, Judy hopes to turn some opinions. We just need some open minds, she says, they have to listen to what we have to say. Some people are just dead set on the electric regardless of what we tell them, and I’m hoping that as we continue to speak about our product, the benefits and security of it, then one by one we’ll start to get the door opened a little bit. Some New England states have already started to entertain the idea that propane is a good compliment to electric, it’s certainly cleaner than coal, which produces a lot of the electric in other states. When it comes to renewable propane, it will be more about the buy-in than the size of the market, once people understand what the product is. Propane is clean, reliable, and portable. It can go where electric can’t go and do what electric can’t do. I think, Judy explains, that marketers all understand that to get their foot in the door, they’re going to have to pay a little bit more initially to get it up here. A costumer who wants to buy in is going to have to pay a little bit more in upfront costs, similar to the person that’s driving the EV, they’re spending more upfront than they would for a gasoline car. There are customers where the environment is more important to them than what they’re driving, and they’ll start to drive the market. Then it’s like anything else, Judy explains, the more we sell, the cheaper it’s going to be, and it will snowball. Judy is optimistic that there won’t be any trouble bringing renewable propane on board when she’s ready to start filling her tanks with it. I think it’ll sell; she says, I know one of my suppliers is considering going all renewable and if they do, then I’m jumping in.

September 2022

By Maisie Melican – VTCCC Outreach Intern

Irene Webster is a case manager for the Association of Africans Living in Vermont (AALV) and the coordinator of the AALV women’s group. AALV is a non-profit, non-governmental organization (NGO), community-based program that helps refugees integrate into their new environment in Vermont as New Americans. AALV acts as a bridge to various services that New Americans might need.

AALV: What is Irene’s role as a case worker?

Irene’s role is to be a support system for her clients, helping them with everyday tasks that might be new and difficult. Things such as opening mail, getting food stamps, or making doctors’ appointments. Having initially registered with AALV as a Swahili interpreter, Irene was interested in becoming more involved with the organization. Soon she assumed the role of case manager, a transition that she says was surprisingly easy. Through her experience as a case worker, Irene has learned how to communicate with different types of people. At first, she simply thought of all her clients as African, without thinking about the individual countries they come from. Now, she’s learned how to approach clients of different cultures and more quickly recognizes the traditions they practice.

Irene works with families and hosts a women’s group, where all the participants are women who have experienced war and extreme trauma. Often these women are shunned in their larger communities, Irene explains, they can be looked at as damaged goods. This group provides a safe space for them to gather. In addition, UVM’s Connecting Cultures works closely with Irene to connect the women with clinicians who can provide them with therapy. During group time they participate in fun activities and get to know more about each other. It’s very important for them to be able to trust and to feel connected, Irene says. She has seen a lot of healing happen as a result of the trust she helps them build.

Transportation Barriers

I spoke with Irene last month to learn more about the transportation barriers that her clients face. I began by asking about the transportation methods that are most popular for her clients.

Once they’ve become established in the area, most of her clients use the bus. When they’re new to the community, she says, it’s mostly rides from family and friends. Then, after they understand the layout, they will venture onto the bus. With rising inflation and interest rates, most of Irene’s clients stick to public transportation instead of purchasing a car.

For the most part, public transportation is easy to use, if you don’t have other barriers. English language ability and the ability to read and write are important for navigating bus routes. Her clients need a lot of hand holding, especially because they can’t communicate with the bus drivers. You also can’t talk about these transportation challenges in isolation from who these people are, what their experiences are, their cultures, economic ability, or family structure. All these things can contribute to their ability to get around. Picture yourself she says, you’ve just arrived from a refugee camp, you’re trying to get integrated into the community, and you must overcome these things that might sound easy for the person who’s grown up here. You must remember one thing in particular, they come from survival mode from their time in refugee camps, and they arrive in Burlington, still in survival mode. Then, once they are given the time and resources to help them understand the bus schedule, it’s easy.